LarryWolfe

Chef Extraordinaire

This is a very very good and in depth article and a must read. I never understood the beer can chicken method for the exact reasons 'Meathead' states in his article.

Debunking Beer Can Chicken: A Waste Of Good Beer (And It Is Dangerous)

Think about this: You've never seen a fine dining restaurant serve Beer Can Chicken, have you? That's because real chefs know it is not the best way to roast a chicken.

Yes, I know Beer Can Chicken tastes wonderful. Yes, I know your neighbors and family think your Beer Can Chicken is fabulous. It is fabulous. What's not to love about roast chicken? Yes, I know there are millions of devotees and some bars and BBQ joints serve it.

Yes, I know there are two books on to the subject, a blog, and scores of gadgets to assist the process. Yes, with the fowl perched comically on its legs seemingly guzzling brew through its posterior, Beer Can Chicken is a showstopper. The two beauties at right were cooked by Steve Navarre, a loyal reader, good cook and fine photographer.

But Beer Butt Bird remains a gimmick and a waste of good beer.

To prove it you have to taste a Beer Can Chicken side by side with one of the better methods I recommend later in this article. If you are unwilling to do that, then please don't tell me how stoopid I am in the comments below. Unless you do a blind taste test, gallus a gallus, you cannot pronounce one method superior. But you can do a pre-tasting in your head if you just think about the logic laid out for you below.

Tellingly, the weight of the beer can afterwards, on a very sensitive scale, is unchanged. This may sound shocking, but in a slow rise from room temp to 165°F, not much beer evaporates, and that means very few flavor molecules.

First, let's look at what beer can chicken gets right

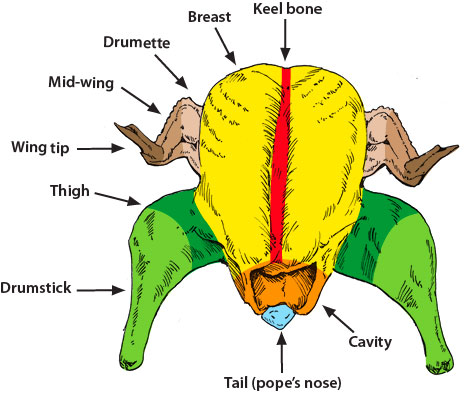

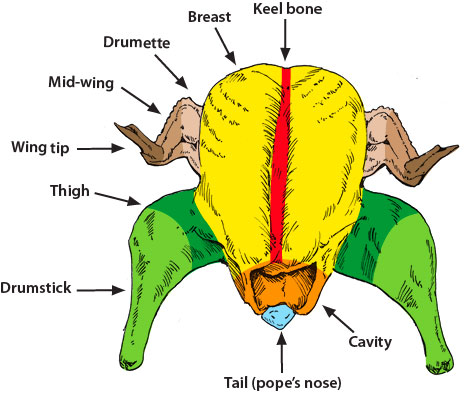

1) Crackly skin. Beer Can Chicken exposes the exterior to even convection heat so it can crisp the skin on all sides. Do it right and you'll always have crunchy, crackly, tasty skin. If you bake a chicken horizontally in a standard roasting pan, the bottom doesn't brown and often gets soggy. Even if you raise it up on a rack, the air does not circulate under the bird properly unless the rack is well above the pan, as it is on a grill.

2) Even exterior browning. Beer Can Chicken doesn't tie the legs together as is done in French roast chicken recipes, so the crotch area can brown properly and the dark meat can be exposed to more heat and finish a bit hotter than the thicker breasts. Chicken and turkey must be cooked to 165°F in order to kill salmonella. But if you go above 165°F you can kill the moisture. So breasts should be removed at about 160°F and they will then rise to 165°F when resting. Dark meat is best in the 170 to 180°F range, depending on your preferences. Vertical roasting lets the dark meat heat faster than the breasts.

Now let's look at the many things beer can chicken does wrong

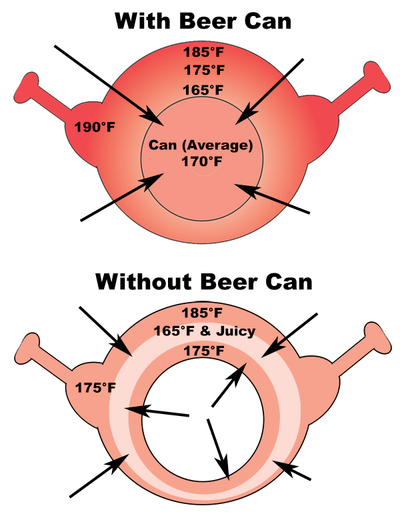

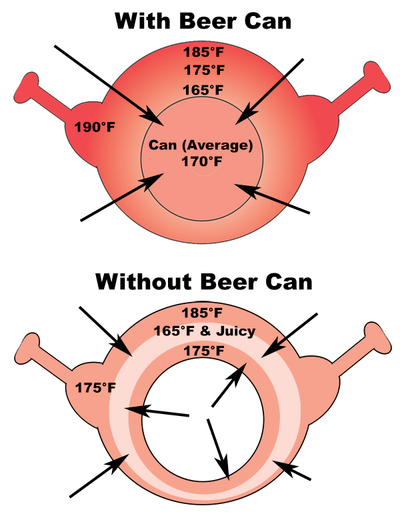

1) All the heat comes from the outside. The thoracic cavity of the bird, where its guts and lungs were, narrows almost to a close at the top. On a typical 3 to 4 pound bird, a 12 ounce can will go all the way up the cavity and rest its shoulders just under the bird's shoulders. In other words, all but a little part of the cavity is filled by the can. There is a much smaller cavity where the neck was, and it connects to the lower cavity with a smaller hole. With a metal cylinder up its butt, warm air cannot enter the cavity from below, and only the tiniest amount imaginable can enter from above. The can effectively prevents the chicken from cooking on the inside. All the heat must enter the meat from the outside. Because meat doesn't heat evenly, it progresses inward from the part in contact with air, the outer parts are warmer than the inner parts. By the time the meat nearest the cavity hits 165°F the outer layers are in the 180 to 190°F range. That may darken and crisp the skin a bit more, but it makes the outer layers drier.

Take away the can and heat enters the cavity and warms the inside of the meat so heat is working its way to the center of the muscles from both sides. This way neither surface gets far overcooked. Remember, air cooks the outside of the meat, but the outside of the meat cooks the inside of the meat. The more meat the heat has to travel through, the more the outer layer gets overcooked. So cooking both sides insures the outer layers are not as hot and not as dry.

2) It only browns on the outside. We love the flavor of browned meats. Browning happens when the amino acids and sugars in meat are heated past a certain point. It is called the maillard reaction and it is the reason we love seared steaks, toasted bread, roasted coffee and crispy chicken skin. By inserting a metal tube filled with liquid you prevent the inside of the chicken from browning, so you get less of the stuff we love best. But the methods I recommend will get you browned chicken all over, inside and out.

Worse, if you cook it at 325°F on the indirect side of the grill, it is hard to get the skin brown and crisp unless you include sugar in the rub, and personally, I just don't think roast chicken is at its best when sweetened. I think roast chicken is best savory, with an herbal rub.

3) No way the beer boils. As you cook, both the meat, which is 70% water, and the beer, which is 90% water, heat at about the same rate. When you are done cooking, when the meat hits 165°F, the beer will also be about 165°F, well below the boiling point of water which is 212°F. Now some of the beer at the bottom of the can may be hotter, but the cooler beer above will mix with it via convection, so there is no way it will come close to the boiling point. There is still some evaporation from the beer at that low temp, but very very little. So, hardly any moisture escapes the can. So how can it moisturize the meat ? And anyone who says it crisps the skin, which is separated from the can by at least 1" of meat really has been smoking more than chicken.

4) No way the beer adds moisture. The method is supposed to add moisture to the meat. But the can is inserted half way up the cavity, so any vapor that escapes the top of the can, and there isn't much, will only come in contact with the upper half of the cavity. The surface area of the exterior of the bird is vastly greater than the surface area of the cavity, and after blocking off half the cavity with the can, there is very little surface area for flavor to penetrate.

5) No way the beer adds flavor. According to Scott Bruslind, Laboratory Manager at Analysis Laboratory, on average, 92% percent of beer is flavorless water and 5% is flavorless alcohol. All the flavor compounds are at most 3.5% of the weight: 1 to 2.5% sugars with 0.5 to 1% a mix of proteins, minerals, small chain organic acids and esters, aldehydes and ketones, which are a mix of acids and alcohols. Finally, 0.25% of the beer is carbon dioxide under pressure to make it bubble.

In other words, in a 12 ounce can of beer, there is about 1 teaspoon of stuff with flavor, even in big dark beers like stout the flavor compounds are a very small part of the brew. Since less than 1% of the beer evaporates during cookingthis is pretty close to nothing. (see the data from research by AmazingRibs.com's science advisor, Dr. Greg Blonder, below). In other words, it is impossible for the beer to flavor the meat in any detectable way.

Alcohol boils at about 170°F, so there may be some alcohol evaporation, but alcohol vapors are not likely to play a role if you remove the chicken at 165°F and even if you overcook, that 5% of ethanol is not going to have much of an impact on flavor. Yes, you can smell beer while it is cooking, but the smell is not much stronger than a beer sitting around at room temp, and that smell is the result of immeasurably small parts per billion of the aromatics. And if the beer is steaming, that means it is at or near 212°F, and that means you chicken is at or near 212°F and it is waaaay overcooked.

And no, it won't make any difference if you use soft drinks or other beverages. None of them will evaporate any faster or contribute any more flavor.

6) Add herbs and spices to the meat, not the beer. John Kass of, a political columnist for The Chicago Tribune raves about beer can chicken. He says you need to put a "hoofta" or two of spices and herbs in the can, the hoofta being a Greek measurement of undetermined quantities, perhaps a handful. The problem is that most of the compounds in herbs and spices don't dissolve in water, but they do in oil and alcohol. But there is not much alcohol in beer. Even then, only a few molecules will escape the can, and most go right out the top.

So what happens if you stuff an onion or lemon in the top? Can you trap more of the beer and herb flavor? You might get a few more molecules of flavor to alight on the meat, but stuffing the vent creates a pressurized area between the can and the blockage, and that will hamper the evaporation of the beer. You want flavor? Paint the cavity with oil and put a hoofta of spice rub in there and let it toast in the warm air without the can.

7) No way a few flavor molecules could penetrate more that a tiny section of meat. Let's say that you use a really high alcohol, dark, flavorful beer like Guinness Stout. Let's say you rub the cavity with a hoofta herbs and spices and salt. Let's say you add a couple more hooftas to the beer and you stick an onion in the neck opening. There is still no way under the heavens that flavor can travel more than a fraction of an inch beyond the surface of the area between the can and the onion. It is against the laws of physics, chemistry and culinary science.

8) The whole process can be dangerous:

•If you forget to open the can, it can explode.

•Some beer can holders use a shallow drip pan that can fill with hot fat. Spill this onto your legs and you'll need an ambulance.

•I've even heard of the drip pan catching on fire and destroying the chicken.

•Spill it onto the flame and for sure you have a chicken crematorium.

•If you use just a plain old beer can, no fancy gadget, getting the the bird and attached can off the grill is tricky. How do you grab it, by the can or by the bird? With what?

•The can tends to stick to the chicken during cooking, and hot grease can build up on the top of the can if you haven't removed it completely. But worst of all, removing the can can be really tricky, and if it jerks out you can find yourself covered in hot beer and scalding grease.

•You must take the meat temp close to the ribs not in the center of the breast because the coldest part is down by the cavity.

•Some beers, like Guinness Stout, have a "widget", a plastic ball in the can that helps release the CO2 in the beer and who knows what it is made of and how it will behave when heated.

•Finally, the ink on the outside of the can may not be food grade and might get into the meat and I sincerely doubt that brewers test the plastic liners inside the can at cooking temperatures. I asked the nice folks at Anheuser-Busch, maker of Budweiser and other popular beers. They said "There are many recipes that cooks have been passing around for years that use beer to flavor chicken, and some of them suggest using an actual can of beer in the cooking process. While many people swear by these methods, and apparently produce some delicious results, it's not one we endorse or recommend, since we don't design our cans for this purpose. We do, however, recommend many recipes using beer and for cooks to be creative with beer in many other dishes as well."

How'd you like some plastic in your hoofta?

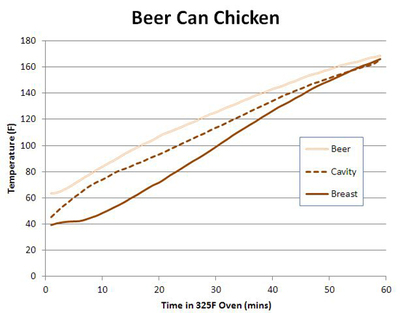

The proof is in the cookingSo I asked the AmazingRibs.com science advisor, Dr. Greg Blonder, to think about all this. He started by roasting three pound chickens at 325°F, the temp I recommend for chicken and turkey. It is low enough to slowly cook the meat without badly overheating the outside layers, and high enough to render fat for crispy skin.

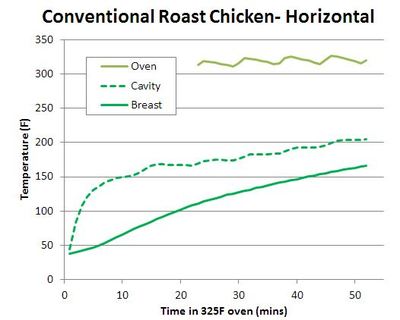

1) Plain roasted chicken measurements. He roasted the birds in an indoor oven where he had better temperature control. He did not put a dark rub on the skin for his tests so they will look paler than many other beer can chickens. He monitored the breast meat temp and the air temp in the cavity with highly accurate thermocouples.

It took the meat just less than an hour to reach 165°F. By that time the air temp in the cavity was about 212°F, boiling temp for water. So by the time the bird was done, the air in the cavity was about 125°F cooler than the air outside. The results were a bird that was " lightly brown and very moist and tender" on the outside, and pale on the inside.

2) Vertical roasted chicken measurements. Next he took a vertical roaster, a stainless steel wire rack with a built-in drip pan beneath it. He repeated the test several times and there was surprisingly little difference in the time the meat took to cook on the vertical roaster and the horizontal roaster. We had expected the vertical alignment of the bird would allow more hot air to enter the cavity.

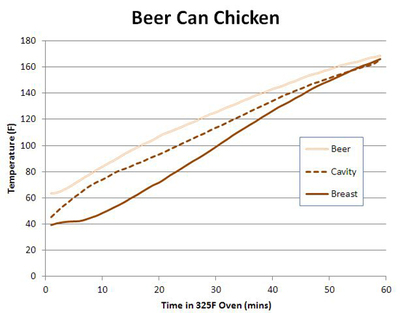

3) Beer Can Chicken Measurements. Then he tested the classic beer can chicken. To make sure there was enough surface area for the beer to evaporate, he poked extra holes, and to make room for 5 crushed cloves of garlic, he drank about 1/4 of the can. That's his story, anyway.

The garlic was added to create a strong aroma that would be easy to taste if it penetrated the meat. He even let the beer come to room temp, more than 30°F warmer than fridge temp, so the beer would not cool the interior of the bird and hamper its cooking. Most cooks don't do this.

Thermocouples were inserted into the breast meat, the beer, and hovering just above the beer. All three rose in temp together and reached serving temp at about the same time, a little more than an hour later.

Tellingly, the weight of the beer can afterwards, on a very sensitive scale, was unchanged. This may sound shocking, but in a slow rise from room temp to 165°F, not much beer evaporates, and certainly fewer of the flavor molecules. Blonder did notice a slight garlic flavor near the neck cavity, but only there.

Click here to see the details of Dr. Blonder's experiments.

In preparing this article I did some Googling and discovered that Doug Hanthorn, the very clever fellow behind TheNakedWhiz.com also set out to test the concept and came up with similar data. His conclusion? Same as ours.

Michael Chu, the author of the excellent website CookingForEngineers.com tested the Poultry Pal, a device that is supposed to improve on the beer can. He came to the same conclusion.

So before you type below how stoopid I am, consider that three scientist/cooks have come to the same conclusion: Overrated.

Six ways to cook chicken better

By far the meat temp is the single most important factor in getting juicy, flavorful, safe chicken. The cooking method is less important. You want to remove the bird when the breasts are 165°F in the center (or against the ribs if you have a can in there). The dark meat should be about 170°F. Dark meat can withstand higher temps and you'll hardly notice it, but overcook the breasts and you have cardboard. With all the money you can save on beer, buy yourself a good digital thermometer. Cutting the meat to look for clear juices is not reliable and the fact is that salmonella is widespread in poultry nowadays.

1) Horizontal roast on the grill. If you just forego the can, lightly oil the entire bird (it helps dissolve the oil-soluble flavors in the spices and herbs), throw a hoofta of seasoning in the cavity, you will get a better bird. But it must be cooked on the indirect side, away from direct flame, in a 2-zone setup. If you want really crispy skin, as the meat approaches 150F you can then move it to the direct heat side and roll it around over high heat for a few minutes.

2) Vertical roast. Blonder likes vertical roasting on the indirect side. "The one thing beer can chicken gets right is vertical roasting. This uniformly cooks the meat, and crisps the skin. As long as you monitor the temperature and catch it when the breast hits 165°F, the meat will be moist and tender. So I strongly recommend vertical wire roasting frames, on the grill or in the oven. And keep the beer where it belongs: In your hand."

3) Rotisserie chicken (right) is better still. Season the interior, and the juices from the rotating bird will roll around the skin but not as many will fall in.

4) Spatchcocked or butterflied chicken (left) is better still. You take the backbone out and flatten it and cook it skin up on the indirect side, and then flip it skin down on the direct side for a few minutes. This browns all parts on all sides, even the cavity. And it looks just as cool as Beer Can Chicken. The one at right was cooked on a gas grill. You can get really dark mahogany skin on a charcoal grill.

5) Halving the bird is better. Remember, these are animals, not widgets, and they never cook evenly. If you cut the bird in half you can use your trusty instant read thermometer and monitor doneness and move legs or breasts closer or further from the heat as needed.

The problem with spatchcocking and halving is that the thighs easily tear off when you move the meat around since there is little other than skin holding it to the breasts.

Pieces kick Beer Butt Chicken in the butt

Cutting the bird into pieces is the best method, if you do it right. The secret is to set up a 2-zone configuration on your grill. This means one side, the direct heat side, is hot with the flame directly below, and the other side, the indirect heat side, has no flame below. You start the meat on the indirect side where it can gently roast from all sides at 225 to 325°F, and the bottom begins to brown. The indirect side cooks by circulating convection flow air. Put wood over the flames on the direct side and you can add another layer of flavor.

You can monitor each individual piece, and if you use a good digital thermometer you will be shocked to see how different they are. You can move each piece closer to or further from the direct heat so nothing overcooks. At about 150°F, you move each piece skin side down to the direct heat hot side and brown it. It is vital that you use the 2-zone system to make this work or the thin edges of the chicken will overcook and the meat will dry out.

Do it right and you will have tender, juicy pieces, brown all over, with each piece cooked to perfection, a feat impossible to achieve if the bird is whole and has a beer can up its butt.

Best of all, you don't have to struggle cutting up a whole hot chicken.

Click here for my recipe for Simon & Garfunkel chicken, which describes this method in detail, and compare it to Beer Can Chicken. To do the comparison properly you must use the same rub on both preparations, and cook them side by side on the same grill monitoring temps with a digital thermometer.

Other tips to improve your chicken: Start by buying better birds, perhaps pasture raised, and then try brining, injecting, and smoking. Lay on the oil and herbs and steer clear of the sweet barbecue rubs.

But if you want to believe in Beer Can Chicken, please ignore the data and please ignore the logic and go ahead and waste your beer. And when you see a Michelin rated restaurant offering Beer Can Chicken, please let me know.

Debunking Beer Can Chicken: A Waste Of Good Beer (And It Is Dangerous)

Think about this: You've never seen a fine dining restaurant serve Beer Can Chicken, have you? That's because real chefs know it is not the best way to roast a chicken.

Yes, I know Beer Can Chicken tastes wonderful. Yes, I know your neighbors and family think your Beer Can Chicken is fabulous. It is fabulous. What's not to love about roast chicken? Yes, I know there are millions of devotees and some bars and BBQ joints serve it.

Yes, I know there are two books on to the subject, a blog, and scores of gadgets to assist the process. Yes, with the fowl perched comically on its legs seemingly guzzling brew through its posterior, Beer Can Chicken is a showstopper. The two beauties at right were cooked by Steve Navarre, a loyal reader, good cook and fine photographer.

But Beer Butt Bird remains a gimmick and a waste of good beer.

To prove it you have to taste a Beer Can Chicken side by side with one of the better methods I recommend later in this article. If you are unwilling to do that, then please don't tell me how stoopid I am in the comments below. Unless you do a blind taste test, gallus a gallus, you cannot pronounce one method superior. But you can do a pre-tasting in your head if you just think about the logic laid out for you below.

Tellingly, the weight of the beer can afterwards, on a very sensitive scale, is unchanged. This may sound shocking, but in a slow rise from room temp to 165°F, not much beer evaporates, and that means very few flavor molecules.

First, let's look at what beer can chicken gets right

1) Crackly skin. Beer Can Chicken exposes the exterior to even convection heat so it can crisp the skin on all sides. Do it right and you'll always have crunchy, crackly, tasty skin. If you bake a chicken horizontally in a standard roasting pan, the bottom doesn't brown and often gets soggy. Even if you raise it up on a rack, the air does not circulate under the bird properly unless the rack is well above the pan, as it is on a grill.

2) Even exterior browning. Beer Can Chicken doesn't tie the legs together as is done in French roast chicken recipes, so the crotch area can brown properly and the dark meat can be exposed to more heat and finish a bit hotter than the thicker breasts. Chicken and turkey must be cooked to 165°F in order to kill salmonella. But if you go above 165°F you can kill the moisture. So breasts should be removed at about 160°F and they will then rise to 165°F when resting. Dark meat is best in the 170 to 180°F range, depending on your preferences. Vertical roasting lets the dark meat heat faster than the breasts.

Now let's look at the many things beer can chicken does wrong

1) All the heat comes from the outside. The thoracic cavity of the bird, where its guts and lungs were, narrows almost to a close at the top. On a typical 3 to 4 pound bird, a 12 ounce can will go all the way up the cavity and rest its shoulders just under the bird's shoulders. In other words, all but a little part of the cavity is filled by the can. There is a much smaller cavity where the neck was, and it connects to the lower cavity with a smaller hole. With a metal cylinder up its butt, warm air cannot enter the cavity from below, and only the tiniest amount imaginable can enter from above. The can effectively prevents the chicken from cooking on the inside. All the heat must enter the meat from the outside. Because meat doesn't heat evenly, it progresses inward from the part in contact with air, the outer parts are warmer than the inner parts. By the time the meat nearest the cavity hits 165°F the outer layers are in the 180 to 190°F range. That may darken and crisp the skin a bit more, but it makes the outer layers drier.

Take away the can and heat enters the cavity and warms the inside of the meat so heat is working its way to the center of the muscles from both sides. This way neither surface gets far overcooked. Remember, air cooks the outside of the meat, but the outside of the meat cooks the inside of the meat. The more meat the heat has to travel through, the more the outer layer gets overcooked. So cooking both sides insures the outer layers are not as hot and not as dry.

2) It only browns on the outside. We love the flavor of browned meats. Browning happens when the amino acids and sugars in meat are heated past a certain point. It is called the maillard reaction and it is the reason we love seared steaks, toasted bread, roasted coffee and crispy chicken skin. By inserting a metal tube filled with liquid you prevent the inside of the chicken from browning, so you get less of the stuff we love best. But the methods I recommend will get you browned chicken all over, inside and out.

Worse, if you cook it at 325°F on the indirect side of the grill, it is hard to get the skin brown and crisp unless you include sugar in the rub, and personally, I just don't think roast chicken is at its best when sweetened. I think roast chicken is best savory, with an herbal rub.

3) No way the beer boils. As you cook, both the meat, which is 70% water, and the beer, which is 90% water, heat at about the same rate. When you are done cooking, when the meat hits 165°F, the beer will also be about 165°F, well below the boiling point of water which is 212°F. Now some of the beer at the bottom of the can may be hotter, but the cooler beer above will mix with it via convection, so there is no way it will come close to the boiling point. There is still some evaporation from the beer at that low temp, but very very little. So, hardly any moisture escapes the can. So how can it moisturize the meat ? And anyone who says it crisps the skin, which is separated from the can by at least 1" of meat really has been smoking more than chicken.

4) No way the beer adds moisture. The method is supposed to add moisture to the meat. But the can is inserted half way up the cavity, so any vapor that escapes the top of the can, and there isn't much, will only come in contact with the upper half of the cavity. The surface area of the exterior of the bird is vastly greater than the surface area of the cavity, and after blocking off half the cavity with the can, there is very little surface area for flavor to penetrate.

5) No way the beer adds flavor. According to Scott Bruslind, Laboratory Manager at Analysis Laboratory, on average, 92% percent of beer is flavorless water and 5% is flavorless alcohol. All the flavor compounds are at most 3.5% of the weight: 1 to 2.5% sugars with 0.5 to 1% a mix of proteins, minerals, small chain organic acids and esters, aldehydes and ketones, which are a mix of acids and alcohols. Finally, 0.25% of the beer is carbon dioxide under pressure to make it bubble.

In other words, in a 12 ounce can of beer, there is about 1 teaspoon of stuff with flavor, even in big dark beers like stout the flavor compounds are a very small part of the brew. Since less than 1% of the beer evaporates during cookingthis is pretty close to nothing. (see the data from research by AmazingRibs.com's science advisor, Dr. Greg Blonder, below). In other words, it is impossible for the beer to flavor the meat in any detectable way.

Alcohol boils at about 170°F, so there may be some alcohol evaporation, but alcohol vapors are not likely to play a role if you remove the chicken at 165°F and even if you overcook, that 5% of ethanol is not going to have much of an impact on flavor. Yes, you can smell beer while it is cooking, but the smell is not much stronger than a beer sitting around at room temp, and that smell is the result of immeasurably small parts per billion of the aromatics. And if the beer is steaming, that means it is at or near 212°F, and that means you chicken is at or near 212°F and it is waaaay overcooked.

And no, it won't make any difference if you use soft drinks or other beverages. None of them will evaporate any faster or contribute any more flavor.

6) Add herbs and spices to the meat, not the beer. John Kass of, a political columnist for The Chicago Tribune raves about beer can chicken. He says you need to put a "hoofta" or two of spices and herbs in the can, the hoofta being a Greek measurement of undetermined quantities, perhaps a handful. The problem is that most of the compounds in herbs and spices don't dissolve in water, but they do in oil and alcohol. But there is not much alcohol in beer. Even then, only a few molecules will escape the can, and most go right out the top.

So what happens if you stuff an onion or lemon in the top? Can you trap more of the beer and herb flavor? You might get a few more molecules of flavor to alight on the meat, but stuffing the vent creates a pressurized area between the can and the blockage, and that will hamper the evaporation of the beer. You want flavor? Paint the cavity with oil and put a hoofta of spice rub in there and let it toast in the warm air without the can.

7) No way a few flavor molecules could penetrate more that a tiny section of meat. Let's say that you use a really high alcohol, dark, flavorful beer like Guinness Stout. Let's say you rub the cavity with a hoofta herbs and spices and salt. Let's say you add a couple more hooftas to the beer and you stick an onion in the neck opening. There is still no way under the heavens that flavor can travel more than a fraction of an inch beyond the surface of the area between the can and the onion. It is against the laws of physics, chemistry and culinary science.

8) The whole process can be dangerous:

•If you forget to open the can, it can explode.

•Some beer can holders use a shallow drip pan that can fill with hot fat. Spill this onto your legs and you'll need an ambulance.

•I've even heard of the drip pan catching on fire and destroying the chicken.

•Spill it onto the flame and for sure you have a chicken crematorium.

•If you use just a plain old beer can, no fancy gadget, getting the the bird and attached can off the grill is tricky. How do you grab it, by the can or by the bird? With what?

•The can tends to stick to the chicken during cooking, and hot grease can build up on the top of the can if you haven't removed it completely. But worst of all, removing the can can be really tricky, and if it jerks out you can find yourself covered in hot beer and scalding grease.

•You must take the meat temp close to the ribs not in the center of the breast because the coldest part is down by the cavity.

•Some beers, like Guinness Stout, have a "widget", a plastic ball in the can that helps release the CO2 in the beer and who knows what it is made of and how it will behave when heated.

•Finally, the ink on the outside of the can may not be food grade and might get into the meat and I sincerely doubt that brewers test the plastic liners inside the can at cooking temperatures. I asked the nice folks at Anheuser-Busch, maker of Budweiser and other popular beers. They said "There are many recipes that cooks have been passing around for years that use beer to flavor chicken, and some of them suggest using an actual can of beer in the cooking process. While many people swear by these methods, and apparently produce some delicious results, it's not one we endorse or recommend, since we don't design our cans for this purpose. We do, however, recommend many recipes using beer and for cooks to be creative with beer in many other dishes as well."

How'd you like some plastic in your hoofta?

The proof is in the cookingSo I asked the AmazingRibs.com science advisor, Dr. Greg Blonder, to think about all this. He started by roasting three pound chickens at 325°F, the temp I recommend for chicken and turkey. It is low enough to slowly cook the meat without badly overheating the outside layers, and high enough to render fat for crispy skin.

1) Plain roasted chicken measurements. He roasted the birds in an indoor oven where he had better temperature control. He did not put a dark rub on the skin for his tests so they will look paler than many other beer can chickens. He monitored the breast meat temp and the air temp in the cavity with highly accurate thermocouples.

It took the meat just less than an hour to reach 165°F. By that time the air temp in the cavity was about 212°F, boiling temp for water. So by the time the bird was done, the air in the cavity was about 125°F cooler than the air outside. The results were a bird that was " lightly brown and very moist and tender" on the outside, and pale on the inside.

2) Vertical roasted chicken measurements. Next he took a vertical roaster, a stainless steel wire rack with a built-in drip pan beneath it. He repeated the test several times and there was surprisingly little difference in the time the meat took to cook on the vertical roaster and the horizontal roaster. We had expected the vertical alignment of the bird would allow more hot air to enter the cavity.

3) Beer Can Chicken Measurements. Then he tested the classic beer can chicken. To make sure there was enough surface area for the beer to evaporate, he poked extra holes, and to make room for 5 crushed cloves of garlic, he drank about 1/4 of the can. That's his story, anyway.

The garlic was added to create a strong aroma that would be easy to taste if it penetrated the meat. He even let the beer come to room temp, more than 30°F warmer than fridge temp, so the beer would not cool the interior of the bird and hamper its cooking. Most cooks don't do this.

Thermocouples were inserted into the breast meat, the beer, and hovering just above the beer. All three rose in temp together and reached serving temp at about the same time, a little more than an hour later.

Tellingly, the weight of the beer can afterwards, on a very sensitive scale, was unchanged. This may sound shocking, but in a slow rise from room temp to 165°F, not much beer evaporates, and certainly fewer of the flavor molecules. Blonder did notice a slight garlic flavor near the neck cavity, but only there.

Click here to see the details of Dr. Blonder's experiments.

In preparing this article I did some Googling and discovered that Doug Hanthorn, the very clever fellow behind TheNakedWhiz.com also set out to test the concept and came up with similar data. His conclusion? Same as ours.

Michael Chu, the author of the excellent website CookingForEngineers.com tested the Poultry Pal, a device that is supposed to improve on the beer can. He came to the same conclusion.

So before you type below how stoopid I am, consider that three scientist/cooks have come to the same conclusion: Overrated.

Six ways to cook chicken better

By far the meat temp is the single most important factor in getting juicy, flavorful, safe chicken. The cooking method is less important. You want to remove the bird when the breasts are 165°F in the center (or against the ribs if you have a can in there). The dark meat should be about 170°F. Dark meat can withstand higher temps and you'll hardly notice it, but overcook the breasts and you have cardboard. With all the money you can save on beer, buy yourself a good digital thermometer. Cutting the meat to look for clear juices is not reliable and the fact is that salmonella is widespread in poultry nowadays.

1) Horizontal roast on the grill. If you just forego the can, lightly oil the entire bird (it helps dissolve the oil-soluble flavors in the spices and herbs), throw a hoofta of seasoning in the cavity, you will get a better bird. But it must be cooked on the indirect side, away from direct flame, in a 2-zone setup. If you want really crispy skin, as the meat approaches 150F you can then move it to the direct heat side and roll it around over high heat for a few minutes.

2) Vertical roast. Blonder likes vertical roasting on the indirect side. "The one thing beer can chicken gets right is vertical roasting. This uniformly cooks the meat, and crisps the skin. As long as you monitor the temperature and catch it when the breast hits 165°F, the meat will be moist and tender. So I strongly recommend vertical wire roasting frames, on the grill or in the oven. And keep the beer where it belongs: In your hand."

3) Rotisserie chicken (right) is better still. Season the interior, and the juices from the rotating bird will roll around the skin but not as many will fall in.

4) Spatchcocked or butterflied chicken (left) is better still. You take the backbone out and flatten it and cook it skin up on the indirect side, and then flip it skin down on the direct side for a few minutes. This browns all parts on all sides, even the cavity. And it looks just as cool as Beer Can Chicken. The one at right was cooked on a gas grill. You can get really dark mahogany skin on a charcoal grill.

5) Halving the bird is better. Remember, these are animals, not widgets, and they never cook evenly. If you cut the bird in half you can use your trusty instant read thermometer and monitor doneness and move legs or breasts closer or further from the heat as needed.

The problem with spatchcocking and halving is that the thighs easily tear off when you move the meat around since there is little other than skin holding it to the breasts.

Pieces kick Beer Butt Chicken in the butt

Cutting the bird into pieces is the best method, if you do it right. The secret is to set up a 2-zone configuration on your grill. This means one side, the direct heat side, is hot with the flame directly below, and the other side, the indirect heat side, has no flame below. You start the meat on the indirect side where it can gently roast from all sides at 225 to 325°F, and the bottom begins to brown. The indirect side cooks by circulating convection flow air. Put wood over the flames on the direct side and you can add another layer of flavor.

You can monitor each individual piece, and if you use a good digital thermometer you will be shocked to see how different they are. You can move each piece closer to or further from the direct heat so nothing overcooks. At about 150°F, you move each piece skin side down to the direct heat hot side and brown it. It is vital that you use the 2-zone system to make this work or the thin edges of the chicken will overcook and the meat will dry out.

Do it right and you will have tender, juicy pieces, brown all over, with each piece cooked to perfection, a feat impossible to achieve if the bird is whole and has a beer can up its butt.

Best of all, you don't have to struggle cutting up a whole hot chicken.

Click here for my recipe for Simon & Garfunkel chicken, which describes this method in detail, and compare it to Beer Can Chicken. To do the comparison properly you must use the same rub on both preparations, and cook them side by side on the same grill monitoring temps with a digital thermometer.

Other tips to improve your chicken: Start by buying better birds, perhaps pasture raised, and then try brining, injecting, and smoking. Lay on the oil and herbs and steer clear of the sweet barbecue rubs.

But if you want to believe in Beer Can Chicken, please ignore the data and please ignore the logic and go ahead and waste your beer. And when you see a Michelin rated restaurant offering Beer Can Chicken, please let me know.